Saving; it’s something we’re all trying to do right now and having to get creative in the process. WoodGreen is no exception. That’s why the outstanding results of an innovative retrofit project to save both money and emissions are so exciting.

How the organization achieved the remarkable results could be a complete game-changer for the non-profit sector, according to Mwarigha, WoodGreen’s Vice-President of Housing and Homelessness Services.

“Like all innovation it’s driven by necessity,” says Mwarigha. “But it’s also driven by a culture of wanting to find new solutions to old problems.”

Old buildings, costly repairs

The issues facing WoodGreen are familiar to anyone involved in the social housing sector in Toronto. The few buildings that are available are aging rapidly and “in dire need of capital renewal,” adds Mwarigha.

The old and inefficient heating and cooling systems break down frequently, making for costly repairs and a lot of unhappy and uncomfortable tenants. Just like any homeowner, non-profits have to budget to make ends meet. Rising energy costs coupled with sudden and expensive repairs don’t make that easy.

“The more you spend on your cost columns for gas, water and electricity, the more it squeezes your ability to even do basic repairs,” says Mwarigha. Toronto cannot afford to lose any of its scarce social housing units, but neither can WoodGreen afford all the costly capital repairs outright. It was time to get creative, laughs Mwarigha.

Real-time monitoring key to success

In 2020-2021, WoodGreen launched a $3-million project to retrofit eight of its community housing buildings most in need of upgraded HVAC equipment and improved water efficiency.

The project was initially funded and structured by Efficiency Capital, with engineering firm Finn Projects and controls firm SensorSuite brought on to develop and implement the innovative plan. Aging HVAC equipment was replaced with integrated energy-efficient systems, while water systems were improved. The SensorSuite system ensured the new equipment was well-monitored and that the systems worked to support one another and never at cross purposes.

Very quickly, the issue of system breakdowns and unhappy, uncomfortable tenants in the 1,000 units in question was effectively eliminated, says Mwarigha. “Now the equipment gives them pre-warnings when there is a problem in the system so we can go fix it before it becomes a real problem.”

Results exceed expectations

The key concept of this project was that the money saved from lower water and energy bills would then be used to pay off the initial loans.

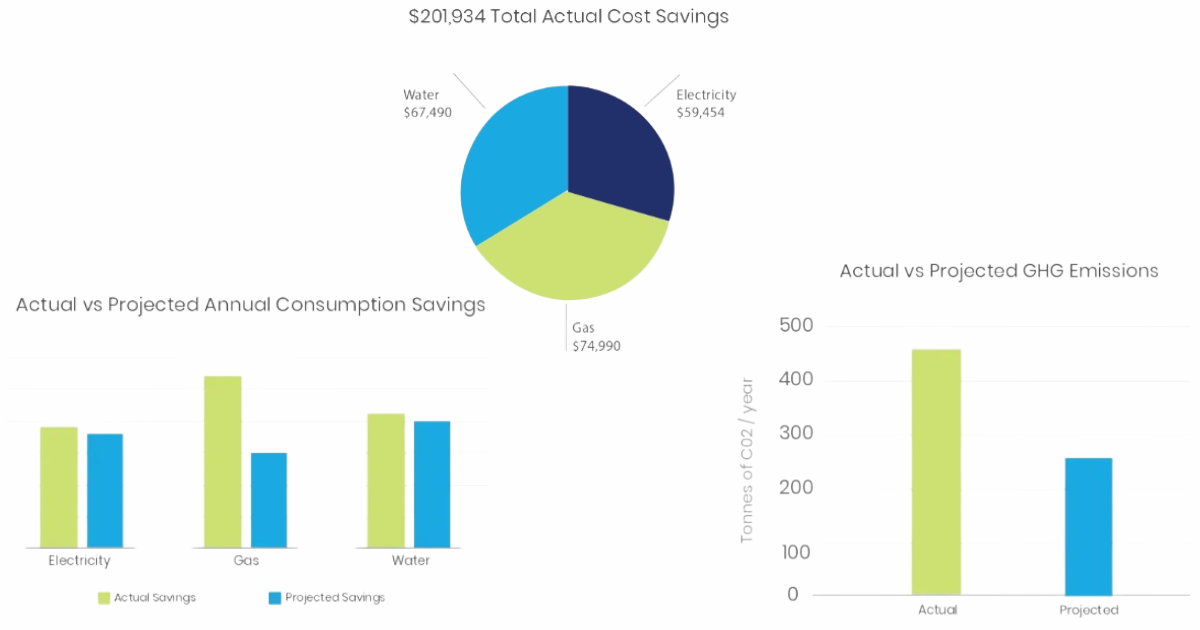

In reality, the plan worked even better than expected! WoodGreen saved 19 per cent in electricity usage, 21 per cent in water usage while gas consumption saved 27 per cent – more than doubling the projected savings. In just the first year with the new equipment, WoodGreen has saved more than $200,000.

In addition to the cost savings, WoodGreen was able to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 450 tonnes, which is 180 per cent of what the team had hoped to achieve. “We are in the process of looking at how we expand the success of this project to other locations.”

Mwarigha says a key component to the success of the project is having a system that accurately measures usage, which is what the SensorSuite controls system provides. The hard numbers are proof, he says, that the energy and cost savings are there. Proof that is vital for what Mwarigha calls the truly innovative part of this project; the way it was financed.

WoodGreen invests in itself

“We have turned ourselves at WoodGreen into a social impact investment,” explains Mwarigha. No longer able to rely solely on government grants or investment in capital projects, WoodGreen used its own financial reserves to partly fund the project as an investment in itself. The money it saves on energy costs is used to pay back both the reserves and outside investors with what Mwarigha says is a solid return rate.

“The key to our innovation is how to monetize energy savings in order to finance retrofit, supported by a robust measurement system and green accounting practice in financial management.”

‘Venture Philanthropy’

If non-profits can show the private sector that they are able to receive a solid return if they invest in a charity’s project, then there will be a great desire to fund such projects, says Mwarigha. In addition, he says it can be appealing to investors that their monetary muscle can be used to do good in their community while at the same time earning them money. This is what Mwarigha says is called “venture philanthropy”.

“We feel proud here,” he says. “As non-profits it requires us to look at ourselves as a kind of an enterprise business model that allows us to be more innovative than the private sector.”

A model for national housing sector

With the impressive returns after just the first year, WoodGreen expects to be able to pay back investors within 10 years. The entire project should have fully funded itself within 20 years.

Mwarigha says the success of this model should be an example for other organizations. The Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation agrees. It has launched a study of WoodGreen’s retrofit project to see if it should be considered a best-practices model across the housing sector.

“If we, as a non-profit, can do it. You for-profits can do it,” says Mwarigha. “By doing so you participate in retaining an affordable housing market because you’re not passing all your major costs into new rents.”